Get Outside - Responsibly

It’s exciting to think that more people are connecting with public lands during the COVID-19 pandemic. Studies have shown that spending more time in green spaces and engaging in physical activity have positive health outcomes for your mind and body. However, there’s now piling evidence to show that we are not taking our environment’s health seriously. The amount of negative impacts people can have on our natural world is nothing new. As if it wasn’t already bad enough prior to the pandemic, the negative human impacts in the forests and waterways are worsening now. The purpose of this blog post is to provide you with three ways you can earn the title of a responsible outdoor enthusiast, but first let me share some of the reasons I care about this topic.

The biggest human impact problem in the outdoors in my opinion is trash. It’s easiest to spot along a back road that otherwise would be quite scenic and serene. But, it’s the hardest bad habit for people to break it seems. Land managers and the avid outdoor enthusiasts alike are noticing that the backcountry trash culture is getting worse as more people flock to find outdoor opportunities as respite from quarantines and for purposes of social distancing. While I like to think it’s universal that trash on trails makes everyone’s blood boil, I know that it doesn’t because I see it out there all the time. Why does it not register with some people that tires dumped into ravines, picnic supplies left behind at overlooks and heavy broken pieces of gear tossed aside or left in shelters along the Appalachian Trail (AT) is NOT OK?

Trash along the Nolichucky River

I know this is not solely a Northeast Tennessee issue as there are people across this country who disrespect our public lands by throwing out trash in our rivers and parks. Also, I realize that trash is of course not the only backcountry problem caused by humans. First responders are burdened with increases in search and rescue missions because more people are outside without the right gear or knowledge of their surroundings. Rare and endangered plants are being plucked or trampled on in sensitive ecosystems. We are seeing first-hand the negative outcomes from human impacts related to fires in the West. Wildlife is being disturbed for photo ops or other unnecessary reasons. And, lastly various user groups are upset with having more traffic from other user groups on shared trail systems.

The pandemic has seen increased visitation to parks - and trash

I’ve noticed that bad etiquette in the outdoors has also become quite a disturbing niche on the Internet that is considered a form of entertainment for people now. There are social media accounts dedicated to showcasing the myriad of ways humans degrade our natural environment. I’m not clear on their purpose most of the time. I applauded them at first because it’s clear that they want to help educate people about behaviors in the backcountry that can be damaging. Now, I realize there’s a darker side to this phenomenon with potential to cause backlash and to drive people away from the outdoors. Some of these accounts take pleasure in publicly embarrassing the folks who are displaying bad behaviors. Bullying and shame is never the answer. This tactic damages a person’s bond with the outdoors and worse could cause someone to double down on their bad behavior in spite. We must focus on the modeling the right behaviors and seeking out the people who wish to be part of the solution. Are you one of those people?

Volunteer Bekah Price cleans out an AT shelter

I’ll also add that no one is perfect or expected to be. I still make mistakes all the time. Mistakes are how we grow and learn. Real change comes when you take responsibility for your actions and choose the path that leads to new outcomes. We must learn how to make change and truly understand why we are doing it. Obviously trash on trails really upsets me, but I try my best to approach these topics with grace and understanding. I tell myself, “After all, these newcomers to the outdoors are probably not educated about the best practices and lack a moral compass in the woods.” We must make it a priority for ourselves that we learn some basics for how to get outside responsibly and take better care of the land.

Volunteers maintaining part of the Appalachian Trail

So, now I offer you three ways in which you can take the path toward becoming a more responsible outdoor enthusiast:

Advocacy – Donate to or help raise money for non-profits that serve the outdoor industry. Call your local, state and federal elected leaders to demand more resources for public land managers to help them enforce and educate the public about proper waste disposal. Most importantly, be a good advocate by modelling good behaviors in the backcountry. You can also find something related to the outdoors that you are passionate about and share that with the world in a positive and unique way.

Stewardship – Become a volunteer trail maintainer or get involved in a volunteer trail work day. Seek out park staff or organizations that would welcome you to assist them in taking care of the land they manage. Seek out educational resources to learn more about the ecology of a specific place or learn more about the natural world in general. Try to find more environmentally friendly ways to accomplish tasks at work and in your daily lives.

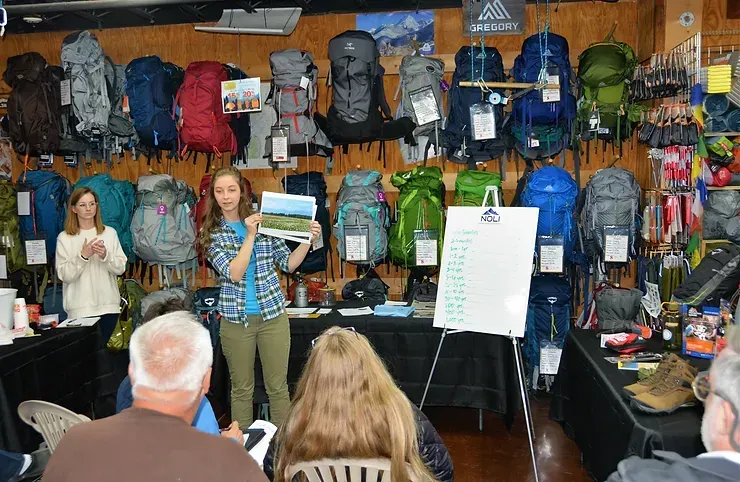

Leave No Trace – And, finally, learn these seven guidelines set forth by the Center for Outdoor Ethics. I can teach you some fun hand gestures to help you remember them all. Actually, I invite you to sign up for my two-day course with NOLI that would earn you a cool badge and pin that says “Leave No Trace Trainer” and then you can go out and teach more people! It’s also a great resume booster. If you’re interested in my class, you can find out more information and sign up here. The next Trainer Course is Nov. 14 and 15. We have limited the capacity to six spots to accommodate added safety precautions during the pandemic.

Girl Scouts pick up trash along the Nolichucky River

Should you not be able to do any of the things I mentioned, I hope just by reading this you take time to think through how much of an impact (positive or negative) that you can make while on your next outdoor adventure. I want everyone to know that the outcomes of human impacts on our environment could mean we lose access and degrade natural areas completely. We can be motivated to change our habits when we are told by a doctor that we must exercise more to live longer. Who is going to motivate you to do the same for the sake of the natural world so that it may thrive and ultimately so that we can survive? We must take care of public lands and waterways like we should take care of our bodies. After all, we are products of our environment and it is what ultimately what sustains us.

Kayla Carter is a Leave No Trace Master Educator and the Outdoor Development Manager for Northeast Tennessee Regional Economic Partnership. She successfully through-hiked the Appalachian Trail in 2014 and helps maintain part of the trail during her free time.