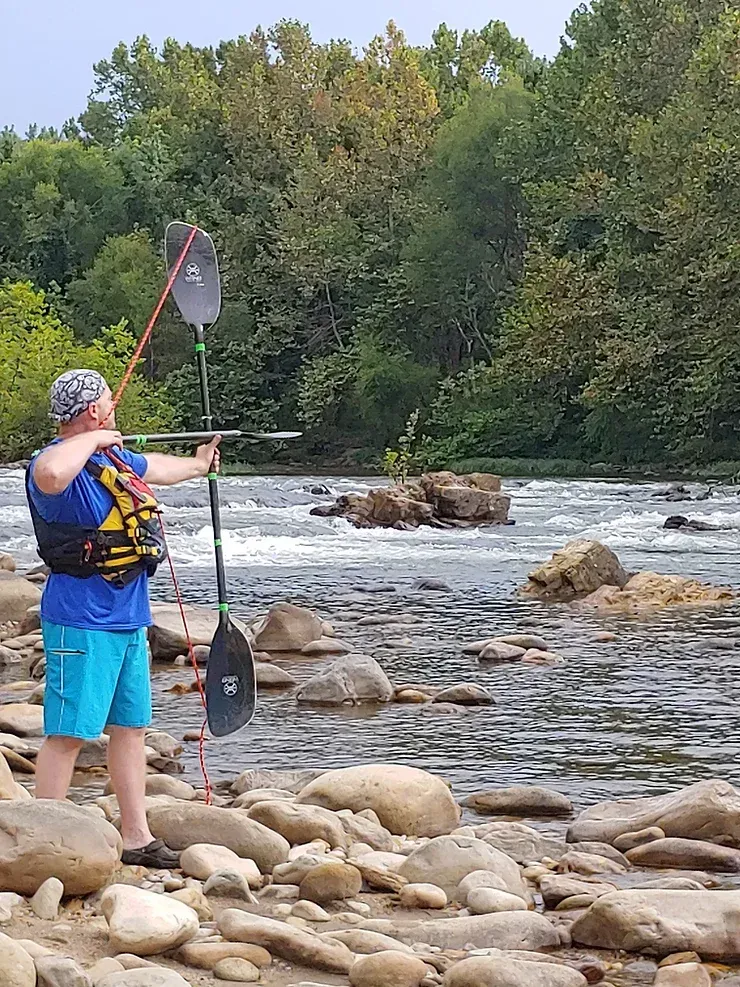

It's NOT the arrow...it's the ARCHER!

During a person’s paddling career, there are many things to consider: how to stay safe, have fun, develop the necessary skills, learn different rivers at different levels, find friends to paddle with that have similar interests and skills, just to name a few.

One of those things you have a lot of input into is… GEAR! Boat shape and style, paddle length and composition, PFD type, helmet brand and color, which high definition camera to use to record your epic run… It’s overwhelming! But there is a factor that supersedes all those considerations.. YOU! You are the common denominator that brings all the gear together to navigate and hammer down on all those sweet river moves.

But hey, I get it, personal paddling skills are arguably the hardest to come by. It takes time. It takes patience. It takes commitment. When it gets hard, or your reach a plateau in your skills progression, it’s tempting to start looking back toward the gear.

Maybe you need more rocker in your bow to punch those sick monster holes? Of course, your planing/displacement hull isn’t really as good as a displacement/planing hull. (That’s a choose your own adventure sentence. Just circle the answers that fit your situation. If you have a planing hull, someone will tell you to get a displacement, and vice versa). Is that REALLY the right offset for your paddle? Of course, if you change up your paddle from wood/fiberglass/carbon to carbon/wood/fiberglass, you’re mad stroke technique will be MUCH better. And on and on…

The truth is, until you can paddle your own boat, the gear cannot provide the fundamental skills required. Those skills come from deep in the hindbrain. It’s the old reptilian part of our brain that manages all reflexive body movements like walking, posture, eye movement, and balance. It’s the same part of your brain that is severely challenged when you’re learning to kayak or canoe. It’s actually the same as when you were learning to ride a bike without training wheels. At first it seems impossible; as soon as your feet leave the ground, gravity wants to bring you back to the earth. Usually there are well meaning adults around telling you all manner of techniques and tricks to keep upright:

“OK.. I’ll get you going with a push… Then pedal like crazy to get some momentum!”

“You’ve gotta look where you want to go. The bike will follow your gaze.”

“Leaning into a turn will help you. You won’t have to turn the wheel as far if you lean into it.”

Sounds a lot like the advice your well meaning friends have told you when you start paddling:

“ OK.. When you get into the current, you have to lean forward and PADDLE! You’ve got to be going faster than the water to maintain control..”

“Look where you want to go! The boat will go wherever you look.”

“Lean into the turns. Using your edges and ‘carving’ will help turn the boat. You won’t have to paddle as hard if you use your edges.”

But until your brain figures out all the subtle and automatic things it has to do to maintain balance and control, you fall over off the bike, or flip your boat. Then one day… one magic and wonderful day… it all clicks, and you can do it! And by ‘do it’ I mean, you can stay up. Then you can start to apply all the great advice you’ve been told. Once you can stay upright, the real learning can begin.

This phenomena is the root behind the saying that, “The only real way to get better is time in the boat.” It takes time for the brain to figure out all the subtleties of being on the river. Moving water is very different to travel over than terra firma. The current and forces under your boat are constantly changing, eddy lines surge, swells pop up under your boat, waves form and crash, and on and on. Your response to these changing phenomena have to be immediate and reflexive.

How fast your brain learns to feel and respond to the river varies greatly from person to person. It varies with things like prior fitness and activity level, overall level of health, age, adaptability, tolerance for risk, fear response, etc. I believe that this process is both what makes paddling super fun (some might say addictive) for some people, and makes it terribly frustrating for others and makes them want to quit. For those that stick with it, it is highly stimulating to the cerebellum, or hindbrain. A stimulated cerebellum is a happy cerebellum. It loves to work and be challenged. The more it learns, the more it wants to learn, and can create a sense of well being that is hard to achieve without physical activity. Activities that require constant balance corrections are particularly good at this.

As your brain works out the autonomic responses, you can help to feed your front brain too. You can keep yourself engaged and entertained by getting excellent instruction. Some of the more voluntary actions like proper stroke technique, how to roll your kayak or canoe, and how to read water features will all help you progress in a safe and effective way. Working with other paddlers, or taking formal instruction, can teach you techniques that will help you step up the challenges to your hindbrain, and accelerate your learning curve.

One day you’ll look back on your paddling career, and remember the days that you could barely stay upright in your kayak or canoe in flat water. You’ll remember the first time you got on a river and how terrifying and fun the first monster Class II+ rapid was you crashed through like a boss. At that point, when you want to change it up a little, you try different boats to see how they respond to strong current, or big holes, or how it can help you catch smaller and smaller eddies in bigger and bigger features.

You’ll realize that YOU are the common denominator. YOU have the skills to get down the river with all manner of gear. The hull shape, paddle style, or other gear only add to your abilities, they don’t determine them. It’s not the arrow that hits the target, it’s the archer. YOU are the archer!

Brad Eldridge is a kayak, canoe and self-defense instructor for NOLI. He is also a licensed chiropractor.